Screens, Research and Hypertext

Powered by 🌱Roam GardenOntologies Instead of Hierarchies

Everything is deeply intertwingled.

I've used a lot of client money on hierarchical taxonomies. Not on creating them, mind you. On various card sorting and user testing that demonstrate what we said in the first place: human knowledge does not fall into neat hierarchies.

It's a point that Ted Nelson makes in Computer Lib/Dream Machines, where he writes:

Everything is deeply intertwingled. In an important sense, there are no "subjects" at all; there is only all knowledge, since the cross-connections among the myriad topics of the world simply cannot be divided up neatly.

Much of information science has devoted itself to the attempt to create hierarchies of knowledge. And yet, most of those efforts have been doomed. Indeed, even the granddaddy of all taxonomies—The Linnaean classification—is the subject of fierce debate between systematists who wish to retain hierarchies and those who argue that a system without ranks better reflects the inherent messiness of biology.

That we naturally think of taxonomies as a hierarchy is pretty reasonable. Information architecture is hardly a new discipline. It got its start in libraries back in the 1600s or so—shortly after printing presses made it relatively inexpensive for universities and wealthy individuals to amass more books than it was reasonable to find simply by looking at the spines.

Of course, a book can be in only one place at a given time. So information architecture needed to specify that you can find book X in location A. Hierarchies work extremely well for pinpointing one thing among lots of other similar things.

But digital content isn't like that. It doesn't live in a place. It is a set of 0s and 1s in a database. It can be displayed on an (effectively) infinite number of screens in infinite combinations, all at the same time.

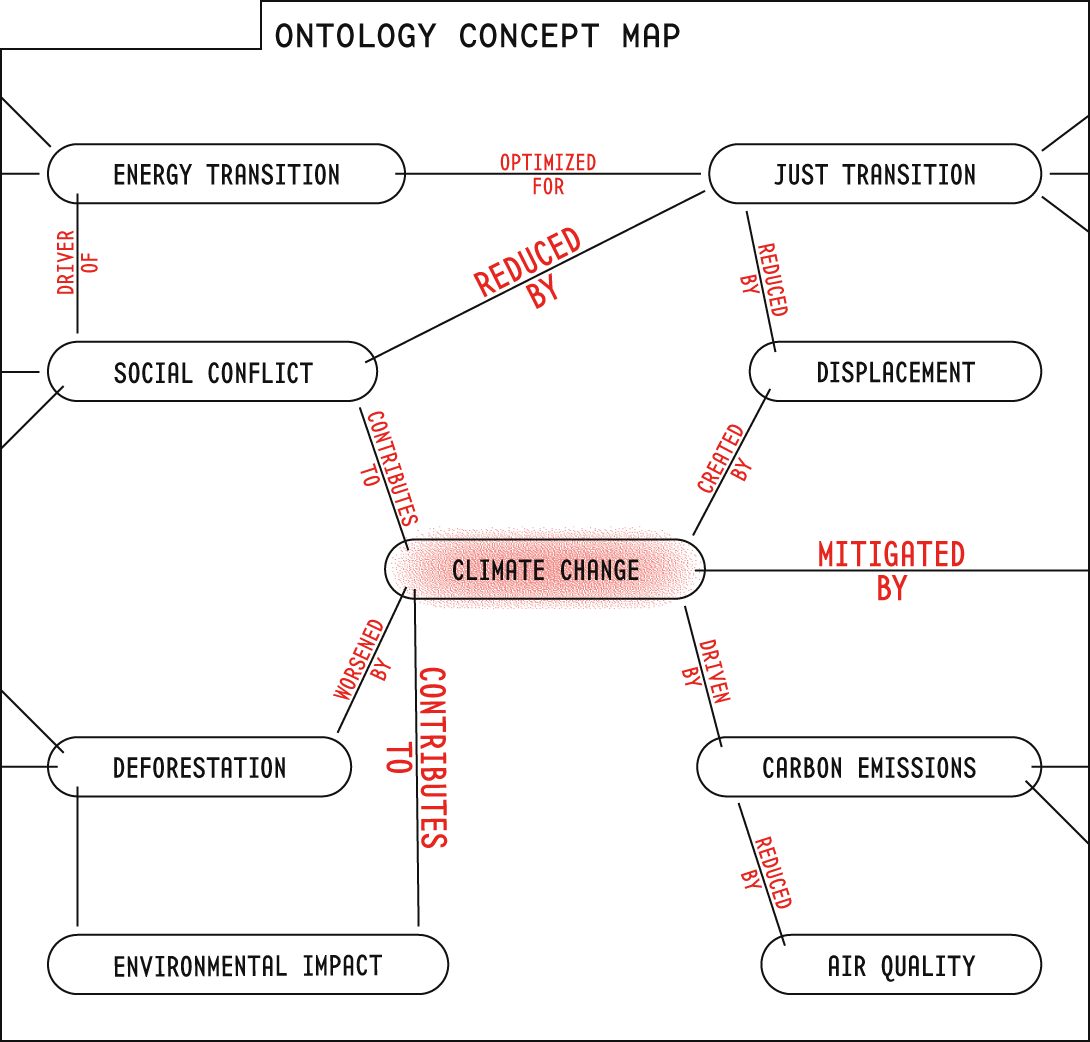

That means we don't need to artificially limit our content to just two relationships—up-down, parent-child, broader-narrower. Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species.

We can, instead, document the many intertwingled relationships between content.

These kinds of conceptual organization schemes are known as ontologies, and they map terms in multiple dimensions. More importantly, they also formally document the relationships between terms. The predicate that links subject term with object term.

For more context

The hyperlink is a key that unlocks the world of intertwingularity.

What to read next

Storing relationships sounds great. How do we do it?

Other items of interest

Categorizing content is as important as creating it.

Ontologies are just one component of a web that's better suited for research.

Hyperlinks document references, not relationships.

Referenced in

Annotating Research Online

The Accidental Taxonomist—still bookmarked with a Christmas tag that marks it as a gift from my brother—filled with notes about the power of ontologies for research content.

Documents Are the Wrong Metaphor

Your content is a bunch of 0s and 1s in a database. There’s no “real” version of it. It doesn’t live anywhere. A bewildering variety of things can come immediately before or after it.

Project Xanadu

For Nelson, hypertext was a way of fully documenting the connections between ideas—of understanding that all of human knowledge is intertwingled. In many ways, Xanadu was to be a computer network that mimicked Nelson's own brain.

Metaphors in Action

But it's less useful when those metaphors lead us to design patterns—like, say, taxonomies that rely on hierarchy—that don't make a lot of sense for digital objects.

The Forms and Limits of Hypertext

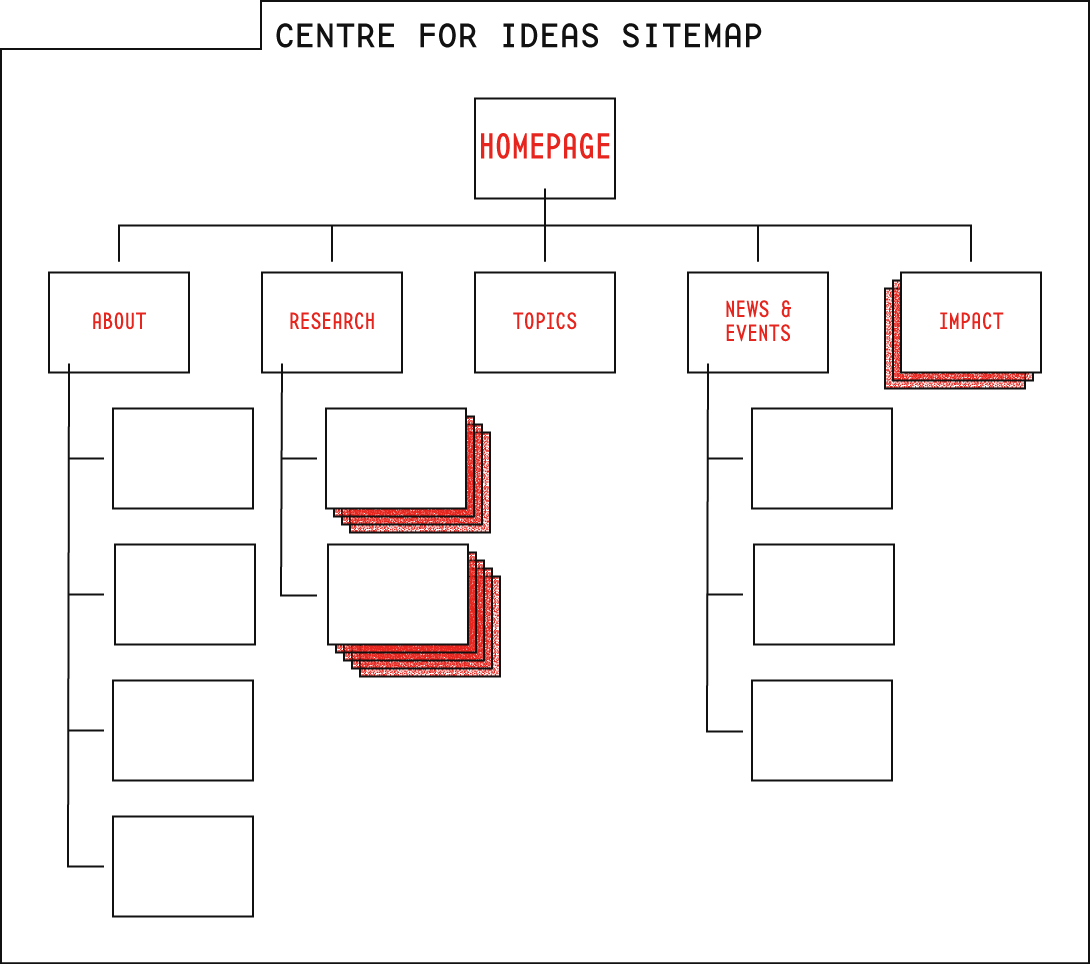

If you rotate this structure 90° clockwise, you’ve pretty much got a sitemap. Indeed, an information architect might call this kind of structure hierarchical — each node is a parent of its connected nodes on the right, and a child of its connected node on the left. Hierarchical language makes a bit less sense when applied to narrative text, so we’ll stick with arborescent.

Transclusions

If you rotate this structure 90° clockwise, you’ve pretty much got a sitemap. Indeed, an information architect might call this kind of structure hierarchical — each node is a parent of its connected nodes on the right, and a child of its connected node on the left. Hierarchical language makes a bit less sense when applied to narrative text, so we’ll stick with arborescent.

Essentials of a Better Web

The document is the fundamental unit of information exchange on the web. Research findings are (usually) collected into IMRAD reports that are (usually) formatted as PDFs. Those reports—whether PDF or HTML—are referenced by a single URL and are (usually) categorized via a hierarchical taxonomy.