Screens, Research and Hypertext

Powered by 🌱Roam GardenTransclusion and URLs

Page-based URLs make transclusion nearly impossible.

The typical hyperlink has a third fatal flaw, through in this case the problem isn't really with the link itself. The problem is that links mostly point to pages. But it's pretty rare that anyone wants to transclude an entire page. Much more common is to include a few words, sentences, maybe even a couple of paragraphs.

In most of the CMSs widely in use in the research sector, URIs don't work that way. Sure, your media files probably have unique URIs. But your text—along with all the other stuff on the page like sidebars and metadata—has just one URI.

Transcluding at anything below the page level requires more granular URIs. And that, in turn, requires writing content that is more modular in the first instance.

A few platforms do this now. Medium, for example, provides a unique identifier for each paragraph. The Nuffield Trust takes a similar approach for its data visualization.

But these are more the exception than the rule. Indeed, many CMSs that feel modular—like the Gutenberg editor for WordPress or Paragraphs for Drupal—really aren't. They still store each module as part of the page's URL.

To be fair, that's a deliberate choice. Drupal and WordPress are web content management systems. Their purpose is to manage web pages.

We can contrast that with a component content management system. These are designed to store content at a modular level, where a module can be as small as a single word or as large as an entire chapter. They typically store all these components in structured XML, a solution that is equal parts extremely flexible and daunting for authors.

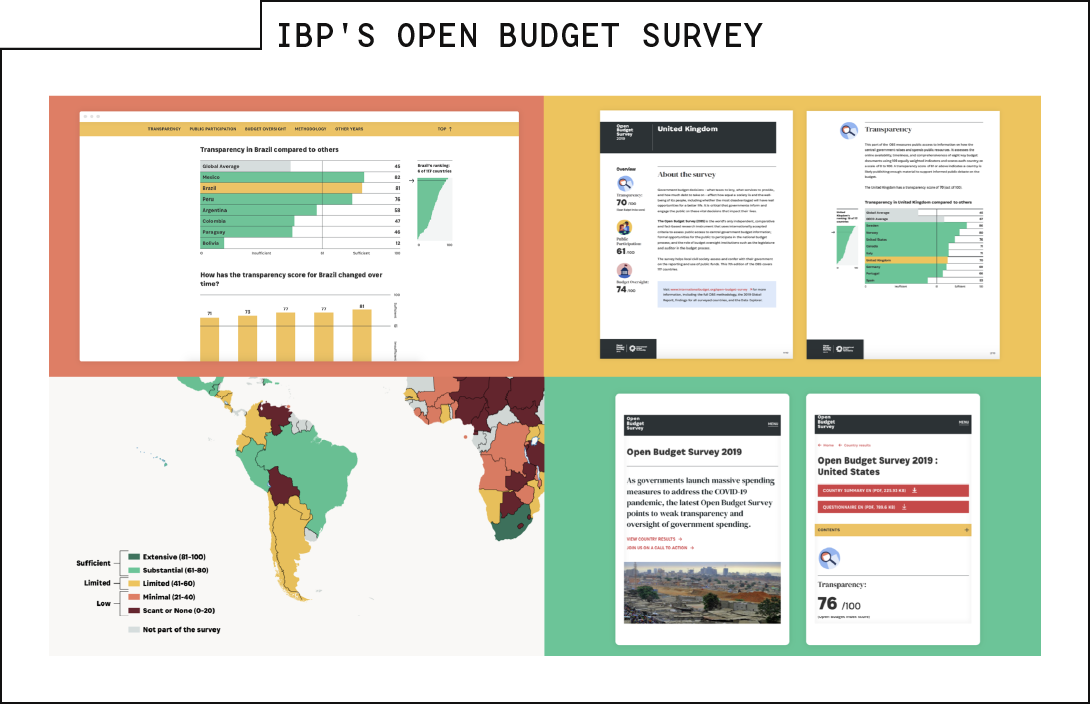

It is possible to combine approaches—the International Budget Partnership has done this in Drupal.

But it's far from standard practice.

For more context

What is transclusion, anyway?

What to read next

URLs aren't the only thing holding transclusion back.

Other items of interest

So URLs are the hyperlink's third fatal flaw. What are the other two?

So URLs are the hyperlink's third fatal flaw. What are the other two?

Better URLs are one half of transclusion. Better writing is the other.

Referenced in

Essentials of a Better Web

The document is the fundamental unit of information exchange on the web. Research findings are (usually) collected into IMRAD reports that are (usually) formatted as PDFs. Those reports—whether PDF or HTML—are referenced by a single URL and are (usually) categorized via a hierarchical taxonomy.