Screens, Research and Hypertext

Powered by 🌱Roam GardenFinding Content Is Changing

No one is using your navigation.

There’s a lot of content on the Internet. Some of the most successful businesses of the Internet era are the ones that provide filters to help us wade through all that content. Search (which is to say Google) lets users enter a topic and then returns a set of pages that contain information about that topic. Social media (mainly Facebook) analyzes our personal relationships, interests, and behaviors, then shows us content that it thinks we will want to see.

To oversimplify a bit, search helps users who are deliberately seeking out specific answers to specific questions. Social media helps users discover things that that are relevant and interesting to them.

Neither filtering method is especially conducive to the way we have traditionally published reports.

Homepages Are Dying

It’s tempting to think of the Internet as a massive series of hub-and-spoke affairs, with each homepage serving as a hub where users land before exploring various internal pages that branch off as spokes. Indeed, that's how websites used to work.

That model does not reflect the reality of today’s Internet use.

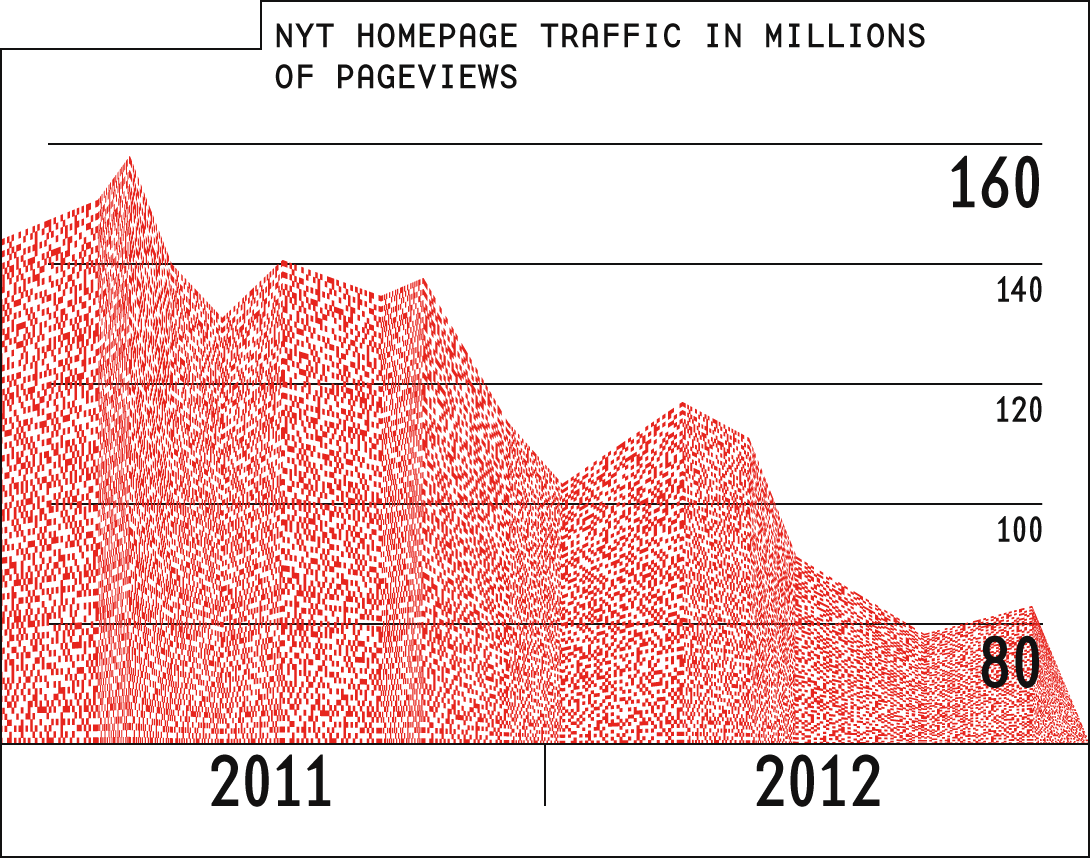

For example, in a much-discussed internal report on its digital strategy, the New York Times revealed that traffic to its homepage declined by about half between 2011 and 2013.

The Atlantic reports a similar trend, noting that in 2012 roughly 90% of the visits to the site began on something other than the homepage. The Atlantic’s Bob Cohn writes that “driving traffic” to interior pages of the site is the one thing that “the homepage is not much good for.”

And yet both The Atlantic and the NYT have seen their web traffic increase even as their homepage traffic has dwindled. For many sites, search and social media referrals account for the majority of traffic, and both predominantly send traffic traffic directly to internal pages.

Social Isn't "Driving Traffic"

As of late 2015, Facebook referrals accounted for 43% of traffic to major media sites. Indeed, new media darlings like Upworthy and BuzzFeed were built almost entirely on Facebook referrals.

That said, the heyday of social media driving traffic to websites has arguably already passed.

Facebook—the juggernaut driving so much web traffic—has made it harder than ever for users to see organic content. Changes to Facebook’s algorithms have reduced the organic reach of “brand” content (aka content that comes from pages rather than profiles) from 16% down to just 2%, meaning that only 2% of the people who like your organization’s page will likely see any given post from that page.

These days, we know that Facebook's algorithms often privilege hate speech and misinformation over evidence-backed research.

Facebook’s changes cut traffic to Upworthy by almost half over the course of two months.

Twitter is even less helpful. An analysis in The Atlantic suggested that the rate of clicks back to an article from Twitter is about 1%. As Derek Thompson writes:

Twitter is worthless for the limited purpose of driving traffic to your website, because Twitter is not a portal for outbound links, but rather a homepage for self-contained pictures and observations.

In other words, Facebook and Twitter—the two sites most government agencies and think tanks rely on for sharing content—are turning into self-contained gardens that users leave less and less frequently.

For more context

Why would I care about Facebook and Twitter? My real content is in a report on my website.

What to read next

Okay, what are we supposed to do about all this?

Other items of interest

I don't buy it. The report just is the way research is communicated.

Nonfiction is linear. What else could it possibly look like?

If people aren't browsing your site, then why do we still build navigation as if they were?

Referenced in

Reporting Progress

The Internet has broken traditional publishing models. The gatekeepers are gone. Your report now competes with a billion publishers creating content across a million channels. And it must find its way to an audience that has adopted entirely new ways of finding and reading content online.